I’m creating this post to help sellers and the public understand the Amazon financial statements and, specifically, the magnitude of anticompetitive pricing (predatory pricing) that has become an essential component of Amazon’s business strategy.

Through various careers and a lot of education, I’ve spent many thousands of hours poring over financial statements. This can be a dense subject, though I’ve tried to include enough images here to make this fairly easy to follow. Likewise, this is not a deep dive into the Amazon financials - it’s not needed for this discussion but you can find a deep dive elsewhere if you’re interested. That said, there is always a degree of uncertainty fostered by a lack of detail in financial statements. While it’s impossible to evaluate and answer the questions we have with 100% certainty, we can get relatively close based on the definitions and figures provided.

Similarly, this won’t be a post that debates predatory pricing definitions. I’ll probably write something at some point to that effect, as I expect it to be a component of the forthcoming FTC suit; however, that would be too much to cover here. For these purposes, let’s just use a basic Google definition - predatory pricing is “the pricing of goods or services at such a low level that other suppliers cannot compete and are forced to leave the market.”

This post is primarily concerned with the extent to which Amazon Retail operates at a loss, such that it has to have income from 3P sellers and AWS sufficient to offset its losses. If you want to follow along, everything is taken from the 2022 Amazon Annual Report which can be found here: 2022 Amazon Annual Report. If the link is broken, go to ir.aboutamazon.com and click on annual reports and you should be able to find it.

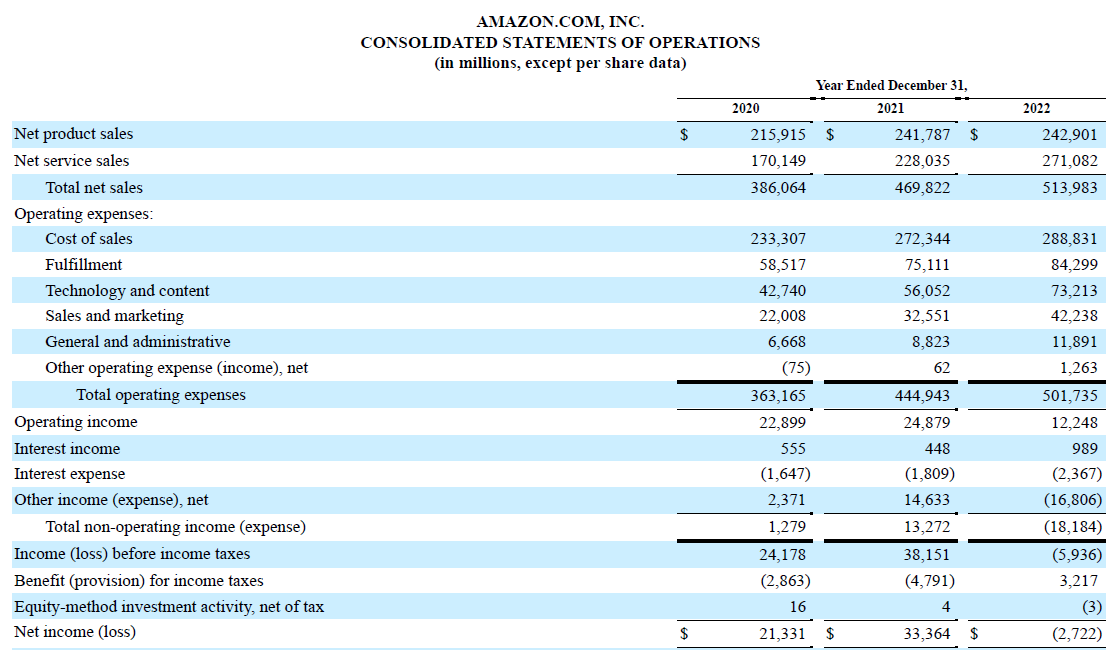

Most dollar figures will be taken from the income statement below, so please familiarize yourself with the layout and column headings.

Net Product Sales

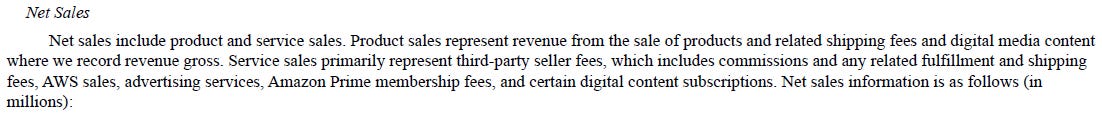

From Page 23, net sales “include product and service sales. Product sales represent revenue from the sale of products and related shipping fees and digital media content where we record revenue gross. Service sales primarily represent third-party seller fees, which includes commissions and any related fulfillment and shipping fees, AWS sales, advertising services, Amazon Prime membership fees, and certain digital content subscriptions.”

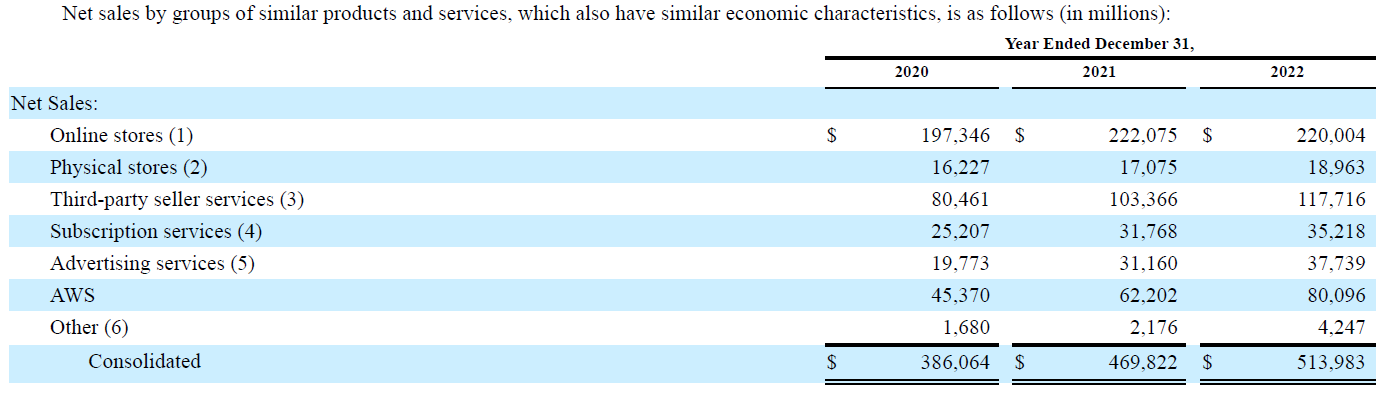

We are primarily concerned with Net Product Sales, which are essentially all first-party/Amazon Retail sales. From the income statement found on page 37, this figure is $242,901 (in millions, so $242.9 billion).

Cost of Sales

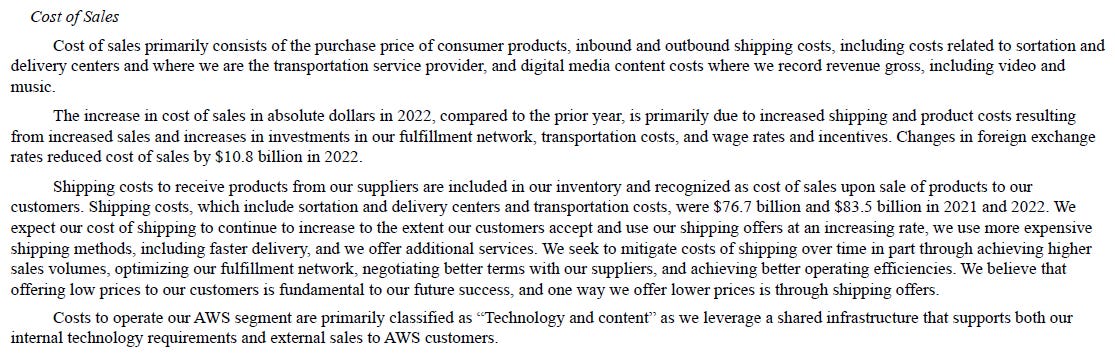

This is a rather lengthy definition, so I’ll try to break it apart. Focusing on the first sentence, cost of sales primarily consists of “the purchase price of consumer products, inbound and outbound shipping costs, including costs related to sortation and delivery centers and where we are the transportation service provider….” You may have noticed on the income statement that fulfillment is a separate expense category. We’ll get to that in a moment. It appears from this definition that cost includes the actual cost paid for the item, inbound shipping (when not provided by the manufacturer), outbound shipping and some sortation costs. Most retailers record cost of goods sold as the cost of the product plus inbound shipping. Because Amazon has so many warehouses to which it must distribute inventory, there’s an added expense; I believe this is categorized as “outbound shipping costs, including costs related to sortation and delivery centers and where we are the transportation service provider.” Though it could be interpreted as such, I do not believe this is a reference to outbound shipping to consumers, but is specifically outbound shipping to other delivery centers/FBA warehouses. The third paragraph details the actual expense of shipping costs in 2022 at $83.5 billion, specifically stating, “shipping costs, which include sortation and delivery centers and transportation costs….” Notably, they do not mention anything here about consumer delivery.

You may have noticed in paragraph two, a statement about foreign exchange rates. Amazon includes a section that deals specifically with foreign exchange rate fluctuations; however, for our purposes, it’s sufficient to just make note of the reduction in cost of sales of $10.8 billion for 2022. I’ll come back to this later when working through calculations.

Fulfillment

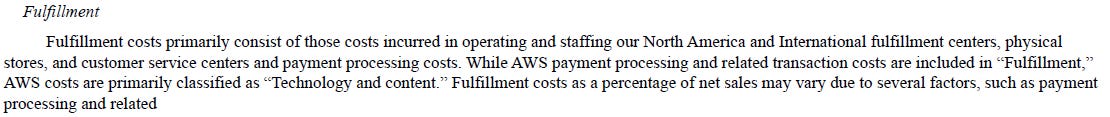

The fulfillment definition straddles a page break; hence, the two images above. It’s pretty clear from the definition that the majority of fulfillment is related to the operation of the FBA warehouses and customer service center. Unfortunately, Amazon includes some AWS expenses in here - payment processing and “related transaction costs.” Payment processing is generally a 1-2% item, so I’ll not dwell on that.

We know that Amazon now handles the majority of their consumer delivery via the fulfillment centers - the staff offices there, the trucks reside there, the inventory is warehoused there, etc. They do mention in the first paragraph the fact they continue to “utilize fulfillment services provided by third parties….” As mentioned above, though they fail to state whether all consumer delivery expenses are categorized here, this is substantial evidence that consumer delivery, whether provided by Amazon or a third party, is expensed under Fulfillment, providing a clearer definition of Cost of Product Sales.

Math

Fortunately, the math is pretty simple. Net Product Sales ($242,901) minus Cost of Sales ($288,831) yields a gross loss of -$45,930, or ($45,930) for the accounting folks. In percentages, this is a loss of 18.9%, meaning items are sold, on average, for 81.1% of cost. Once we adjust for the foreign exchange affect on costs of sales - that I mentioned above - of $10.8 billion, Cost of Sales increases to $299,631. This yields a gross loss of -$56,730, or -23.4%, meaning the average item sold by Amazon Retail is sold at approximately 76.6% of cost.

The reality of the predatory pricing issue is, of course, quite a bit worse. We have allocated no other expense to our calculations. Amazon Retail represents about 40% of Amazon product sales, with the other 60% being attributed to third-party sellers. If we allocate 40% of the remaining expenses (other than Technology as it is largely an AWS expense category on which we have little detail), we see that the real losses of Amazon Retail are somewhere between $110B and $120B, perhaps as much as 50% of Net Product Sales.

Though it’s hard to be 100% accurate here, it’s apparent that Amazon Retail operates at a huge loss, measured in the tens of billions. Notably, despite losing so much money, you may have noticed that Net Product Sales increased a mere $1.1 billion, or less than half of one percent, from 2021 to 2022. Meanwhile, Amazon spent an additional $16.5 billion in Cost of Sales to obtain that additional $1.1 billion in sales. Why would any company do this? Well, that gets us to the business plan part of this discussion.

Predatory Pricing is the Business Plan

There’s a huge amount of pressure on Amazon to appear to be a growth company. Growth is generally evaluated as an increase in revenue, quarter over quarter, year over year. The investor consensus is that Amazon is a growth company and should continually display additional growth in revenue. Investors currently value Amazon at over 100 times annual earnings, or more than 100 years of earnings. This only makes sense so long as it appears that Amazon is growing rapidly such that it won’t actually require 100 years to realize those earnings. The current market capitalization is $1.4 trillion, about what it was a year ago. Late last year, partially due to the figures reported in the 2022 annual report and earlier quarterly reports, Amazon’s share price traded as low as $81, or about 60% of its current price. This was due to concerns that Amazon’s growth might be slowing. It has since nearly doubled, or reverted to the price from last summer. Every quarterly and annual financial release from Amazon focuses on revenue growth, usually detailing a variety of specific segments of growth. Rarely do these announcements highlight expense increases and losses; one is left to dig for those details. This is the reason that a retailer might spend an additional $16.5 billion in cost of sales in order to generate an additional $1.1 billion in revenue.

In the most recent quarterly release (2023Q2, found here), Amazon first highlights a Net Sales increase of 11%, or a $13.2 billion increase. CEO Andy Jassy commented, “it was another strong quarter or progress for Amazon…we continued lowering our cost to serve in our fulfillment network, while also providing Prime customers with the fastest delivery speeds we’ve ever recorded.” The press release goes on to mention AWS growth, the anticipation of Thursday Night Football, a number of Prime movie and TV releases, their 68 Emmy nominations, a variety of international video releases, etc. There’s a section titled “Obsessing over the customer experience” and another one titled “Inventing on behalf of customers.” There’s even a section on the money Amazon gives away and their numerous rankings at or near the top of every employment, innovation and trust survey. Investors cheered and the stock rallied 10%, or about $130 billion, in the two days after the release.

What Amazon and Jassy fail to mention in their press release, though it’s there for anyone with the time to do some math, is that Amazon Retail/Net Product Sales increased only 4.3% and that Cost of Sales increased 4.4%, or about $492 million more than Net Product Sales. Meanwhile, Net Service Sales (AWS and 3P Seller fees) increased 16.5%, or almost $11 billion. Jassy did a sufficient job containing other expense increases, such that the bottom line increased to about $7.5 billion, from a loss of $2.6 billion in the same quarter last year, a swing of roughly $10 billion, or about the difference in additional Amazon Retail losses and additional income from third-party sellers and AWS.

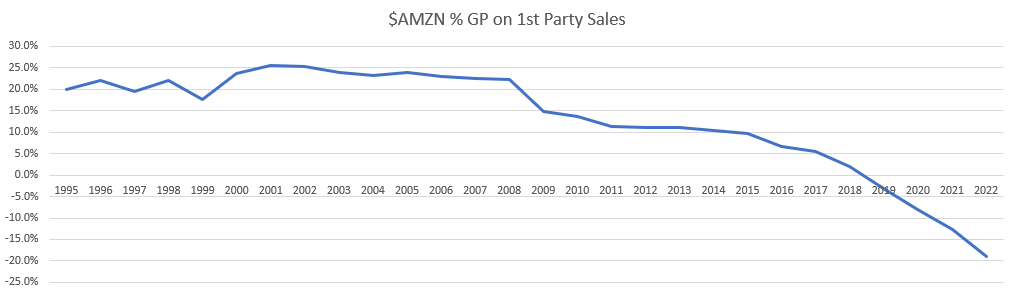

What does all of this mean? Because the Amazon stock price is dependent on continual top line revenue growth, the business itself is dependent upon the same. Because Amazon Retail operates at a gross loss, Amazon must generate enough income from AWS and 3P seller fees to offset those losses plus all other expenses in order for the company to break even. Given Amazon needs to continually show growth of Amazon Retail revenue (Net Product Sales), there is a point at which that additional growth costs more than it generates. Amazon crossed that threshold in 2019 and has continued to magnify Amazon Retail losses each year since. Whereas predatory pricing was once merely a component of their market domination efforts, originating famously in the book market (they actually operated at a relatively healthy 20-25% gross profit from 1995 to 2008), it is now the only source of revenue growth for Amazon Retail and it gets more expensive each year. The chart below illustrates gross profit/loss percentage for each year since Amazon’s public debut.

Because sale prices are usually the result of a formula using cost plus a percentage, normal retailers have a relatively level line varying by only a few percentage points annually, similar to the Amazon period between 1995 and 2008. Indeed, even bankrupt retailers generally operate at positive gross profit. I’m not sure another example exists of a retailer operating at a gross loss for more than a few months. Amazon can only afford to do this by charging ever more fees to third-party sellers and customers of AWS. Where advertising on Amazon barely existed a few years ago, and virtually every search result was organic, it now accounts for almost $38 billion in revenue, generating more ad revenue than any traditional media company or the entire global newspaper industry, according to Ben Evans.

This is likely the most profitable segment within Amazon given it consists mostly of selling space within search results that cost virtually nothing to produce. It has quickly become a necessary expense for anyone wishing to launch a new product on Amazon and is a major additional source of fees for third-party sellers.

Advertising dollars combine with third-party seller fees, Prime subscriptions and AWS income to offset the losses from Amazon Retail. This is the business plan at Amazon. It is by far the largest example of predatory pricing in history and perhaps the only significant long-term example.

The Amazon predatory pricing model has irreparably harmed many thousands of retailers, it has the ultimate effect of reducing competition, innovation and selection, and it creates a two-tiered pricing structure on Amazon, leaving third-party sellers incapable of competing directly with Amazon.

Fantastic analysis, Nick! We're a long time (since 2010) 3P Amazon seller that moved 2m units on the platform in 2020. I've never regretted my past success so much as this year, where I find myself with a pile of inventory and overhead, and a never-ending avalanche of Amazon fees and pay-to-play ad schemes that has eroded our margins to the point of insolvency. We are hanging on for dear life, but it's terrifying. I've been baffled by their seeming eagerness to kill off the golden gooses of 3P sellers (simultaneously jacking fees sky-high while enforcing price-parity, and hoping no one drops the hammer), but your article puts it in a new light - they are topline growth addicts, and they can't help it. It's going to be a bumpy ride, I sincerely appreciate you bringing your expertise to this issue.

Great piece.

Why is Amazon so fixated on their share price? I understand that the c-suite execs make their living from rising share price but is there another reason as well? I guess its as much about predatory pricing and keeping market share as it is growing market share but am I missing anything?

If Amazon isn't a monopoly and market-abuser these words have no meaning.